The safety of workers should be part of the mission of your organization. If it isn’t, do something about it!

The fact is, shop safety in the U.S. and Europe has dramatically improved over the past few decades. Many unsafe acts accepted in the past are forbidden today. The idea of working without fall protection or lockout-tagout (LOTO) procedures is widely condemned by workers, management and supervision. Still, too many people get grievously hurt or even killed at work.

Many thinkers on this topic have identified core approaches. Some include behavior-based safety, a hazard and operability study (HAZOP) design for process safety, job safety analysis (JSA), and others.

This two-part series concentrates on:

- Risk management

- Conditions that are unsafe;

- Contributors to accidents;

- Specific safety for maintenance shops of all kinds.

Each group in an organization, from top management on down, contributes to make a shop safe. Along with that, each group is accountable for part of the safety situation. In fact, a safe shop depends on safety being discussed and being consistently applied at every level in the organization.

Part 1 discusses risk management and the tools to approach and manage any risk (hazardous, operational, financial, etc.). Most professionals know there is a relationship between reliability and safety. In Part 1, we will explore the reasons that reliable equipment is safe equipment. One way to look for hazards is to list all possible hazards. To that end, we provide a hazard list with mitigation. Finally, when looking for safety, we should think about all the conditions that can produce hazards and manage as many as we can.

One Lapse in Judgment Is All It Takes

The most common group to get injured are new hires. But, another big group are those who have 15 or 20 years on the job and have a momentary lapse in judgment.

That’s why it’s so important for organizations to keep reinforcing safe practices, so they are on everyone’s minds when they go to work.

The Goal: Get people thinking and participating. Make safety fun, interesting and be sure to get people’s attention.

Safety and Risk Management

Safety is part of the bigger topic of risk management. According to the book,

Managing Maintenance Shutdowns and Outages, the three steps of risk management that are part of the planning process are risk identification, risk quantification and risk response. The first two, identification and quantification, are sometimes grouped together under risk analysis or risk assessment.

•

Risk identification: Is there a risk here? Address both internal (those under the team’s control) and external (outside world) risks.

•

Risk quantification: How much money will the event cost the organization? How much time will it delay the completion? What is the likelihood of the risky event happening? How many people will get hurt and how hurt will they get?

•

Risk response: What is the response? How costly is it to respond? How likely will the response eliminate the risk? Can the risk be transferred to someone else (e.g., fixed price contracts or buying insurance)? Does the response introduce any unanticipated risk?

•

Risk vigilance, once you are underway: How do you organize your team so that when a risk becomes apparent, you find out and have enough time to respond? In addition to vigilance, this includes responding to changes in the character of the risk over the life span of the project.

Risk management, including risk identification, is best done as a team. This way, people from different backgrounds will see different potential hazards. Imagine the input of millwrights, riggers, operators, engineers, as well as safety people, to the risk equation. Hazards and accidents are two types of risks to be managed!

Reliability and Safety

Reliability and safety are directly related. Reliable equipment is safer equipment for four primary reasons:

Reason 1: Reliability reduces the need to put one’s personnel into harm’s way to fix the equipment. Many accidents are due to being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Those wrong places are on ladders, confined spaces, working hot and various other places maintenance personnel find themselves doing repairs. Reliability keeps people closer to safe areas more often.

Reason 2: The size and scope of the repair is smaller due to preventive maintenance (PM) making for safer repairs. People know that maintained equipment breaks down less often. This is because well maintained equipment has tightened bolts, is properly lubricated and is kept clean. Most failures are the direct result of breakdowns in these three activities of PM. Periodic, on-line or condition-based inspection is another important PM activity essential to safe repairs. This inspection detects defects, damage and deterioration before failure. The size and scale of repairs on problems detected before failure is smaller, lighter and easier to work on.

Reason 3: Hazards are eliminated or mitigated in the planning process. ExxonMobil studied its maintenance related accidents and found: “Accidents are five times more likely while working on breakdowns than they are while working on planned and scheduled corrective jobs.”

High reliability also implies that maintenance planners have time to properly plan the job. One aspect of planning is considering all the hazards and then figuring out and describing a way to accomplish the work safely. The job plan an experienced planner develops reflects the safe way to do the job.

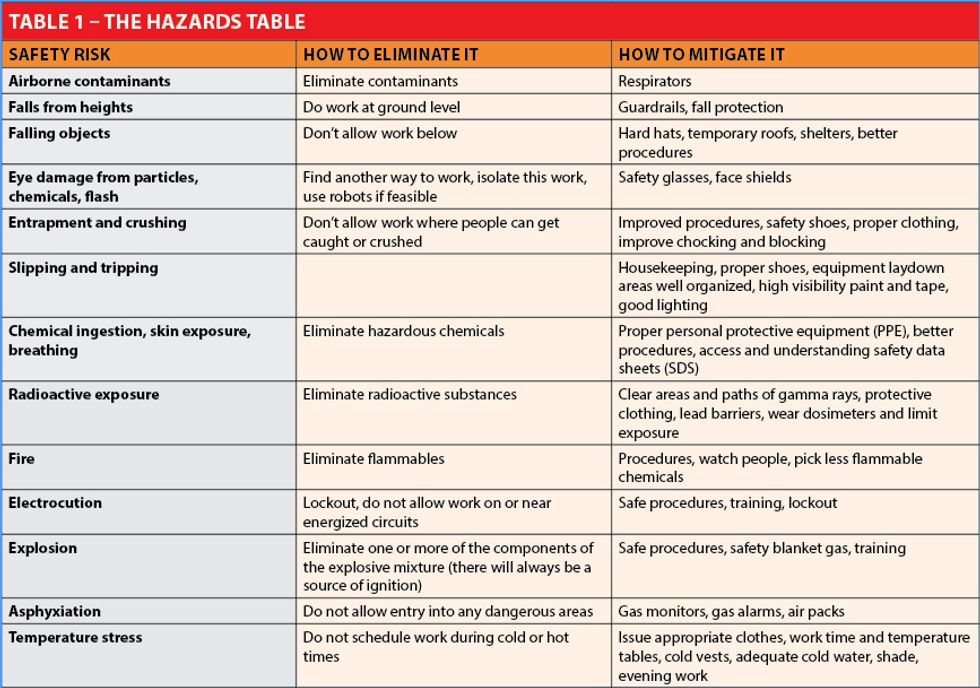

A planner should look at every job and see if any common hazards are present. Hazards include: Airborne contaminants; falls from heights; slipping and tripping; falling objects; eye damage caused by particles, chemicals or flash; chemical caused by ingestion, skin exposure, or breathing in; asphyxiation; radioactive exposure; fire; explosion; electrocution; entrapment and crushing; and temperature stress.

Every hazard identified is either eliminated, which is the best route, or mitigated, which is the second best option. The safest plants are those where the safety of workers is considered at every step in the job preparation process.

Reason 4: Planned jobs have fewer opportunities for the maintenance worker to improvise. Improvisation is statistically less safe than following a job plan with the correct tools and spares.

One of the building blocks of a reliable culture is adequate maintenance planning. Without planning, workers are forced to make do with what spares and tools they can find. To do their job, they may have to improvise to make things work. Improvisation might be great in the theater but can be deadly in maintenance.

Either you can plan and schedule your maintenance activity or your machines will! High reliability is part of a bigger picture of intentional maintenance. Intentional maintenance is where the maintenance effort determines its own schedule, not the breaking machines.

Reliability is the outcome of this intentional maintenance environment and is essential for a safe environment.

Specific Action Items Relating to Reliability

Mechanical integrity programs are difficult to measure directly. Management action items to transform the culture require minor modifications to the weekly and monthly key performance indicators (KPIs) used to run the plant or facility and award bonuses.

Some examples of specific action items are:

- Ratio of emergent maintenance work to planned and scheduled maintenance work should be maintained above 80 percent planned and scheduled.

- PM performance above 95 percent. More than 95 percent of the PMs generated are completed in +10 percent of the PM interval or 30-day PMs completed in between 27 and 33 days.

- Schedule compliance above 85 percent. This means more than 85 percent of the jobs scheduled are completed sometime during the week they are scheduled.

- Mean time between failures (MTBF) for major assets are on an improving trend.

Wider View: The Hazards Table

Table 1 is a reference hazards table that contains a list of all known hazards at most sites. In managing risk, there are four options:

- Accept it and do nothing;

- Remove or eliminate the risk;

- Mitigate the risk by reducing the severity or consequences;

- Transfer the risk, such as buying insurance, vendor contract, etc.

The hazards table also provides examples for eliminating the risk and mitigating the risk for each hazard.

When any of these hazards come into play, you have an accident. An accident is almost never a truly accidental, random event, but rather the result of a cascade of events or causes that end up in damage or injury.

Accidents and Quality

This section is a parallel conversation with quality. It turns out that eliminating the causes for accidents also addresses many of the causes of mistakes and quality problems.

What Causes Accidents?

The dictionary definition of an accident is: “An unfortunate incident that happens unexpectedly and unintentionally, typically resulting in damage or injury.” There are many common causes for accidents in the workplace. Some accidents have overlapping causes and accountabilities.

Here is a list of some of them.

Management

- Unrealistic expectations, pushing too hard

- Not enough money or time to do the job correctly

- Mentality to cut costs regardless of consequences

- Mentality to ignore advice of maintenance, engineering and reliability professionals

- Poor planning

- Not demanding safety be discussed and dealt with at every stage of an activity

- Acceptance of temporary repairs with no plans to remediate

- Interruptions from managers

Processes and procedures

- No risk management

- No hazard identification

- Boiler plate LOTO to try out

- Ineffective hazard permitting (i.e., hot work)

- Lack of a permit to work system, when needed

- Inadequate PPE for level of hazard

- Different rules for management when they are in the shop

- Adherence to rules optional

Supervision

- No instruction

- Bad instruction (i.e., didn’t communicate)

- Incorrect instruction

- Absent supervision

- Bad supervision

- Improper scope, no scope, wrong scope

- Bad communication between trades or shifts

- No wiring schematics

- Supervisor not standing for safety

Engineering

- No drawings

- Drawings wrong

- No as-built drawings

- No operations and maintenance (O&M) manual

- Equipment operated beyond design capacity

- Equipment being used for something it was not designed to do

- Bad design for use

- Designed with difficult access

- Badly designed equipment piping, wiring, or foundation

- No testing, no commissioning

- Old equipment at end of life cycle with multiple unfolding failure modes

Operations

- No standard operating procedures (SOP)

- Lots of short cuts and tribal knowledge needed to operate

Figure 1: Examples of items that mitigate hazards (left to right): Material and safety data sheets and books on how to handle hazardous materials and what to do if exposed to chemicals, lockout station with locks and tags to reduce the chance people will forget and eye wash station to reduce potential damage

Figure 2: A flammable cabinet minimizes, but does not eliminate, the risk of fire and reduces the potential impact

Conditions of people who can contribute to accidents

- People untrained (i.e., ignorance)

- Trained people without experience (i.e., new graduates)

- Trained people without confidence

- Anger at company (i.e., sabotage)

- Low morale, don’t want to do the work

- Bad attitude (rare by itself, usually accompanies another cause)

- People who don’t have the capability (e.g., intelligence, strength, flexibility, endurance, visual and auditory acuity)

- People feeling frustrated and making mistakes, such as not being able to locate things

- People are drugged, legally or illegally

- People are drunk, hung over

- People are preoccupied by things outside of work

- People are preoccupied by things at work (e.g., personal conflict, layoff, merger, etc.)

- People are tired from long hours or moonlighting

- People dehydrated, low blood sugar

- People off their normal prescription medications or adding new medications

- People currently sick or not completely healed

- Injury not healed yet

Tools

- Wrong tools

- Broken tools

- Cheap tools

- Inadequate capacity of tools

- Improvised tools

- No tools

- Don’t know how to use tools available

- Lack of PPE

Materials (e.g., parts, disposables, consumables, free issue, etc.)

- No material, lack of enough material

- Wrong material, but right part numbers

- Wrong material, wrong part numbers

- Slightly wrong material (i.e., make it fit or adapted to work)

- Cheap materials

Working conditions

- Bad lighting, such as too dark, wrong color for work

- Need for magnification

- Slippery

- Bad air, smells, chemicals

- Dusty

- Bad or inadequate work platforms

- Too hot or too cold

- High humidity

- Full sun

- Rain, snow, sand or dust storm

- Lightning, storms

- Graveyard shift

- Working at heights with fear of heights

- Other environmental factors

In Part 2, we descend from the 10,000-foot level of safety and start looking at specifics. These include techniques of job safety analysis (JSA), a look at specific nd statistics, and finally, shop inspections. Our goal is that everyone returns home in the same state that they arrived at work in.